22 Jan Better Data Allows IFSAC and CDC To Identify Sources of Food Poisoning

MedicalResearch.com Interview with:

LaTonia Richardson, PhD, Statistician

Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, Enteric Diseases Epidemiology Branch

CDC

MedicalResearch.com: Who is IFSAC?

Response: The Interagency Food Safety Analytics Collaboration (IFSAC) was created in 2011 by three federal agencies—the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (USDA-FSIS)—to improve coordination of federal food safety analytic efforts and address cross-cutting priorities for food safety data collection, analysis, and use. The current focus of IFSAC’s activities is foodborne illness source attribution, defined as the process of estimating the most common food sources responsible for specific foodborne illnesses. For more information on IFSAC, visit https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/ifsac/index.html.

MedicalResearch.com: What is the background for this study?

Response: Each year in the United States an estimated 9 million people get sick, 56,000 are hospitalized, and 1,300 die of foodborne disease caused by known pathogens. These estimates help us understand the scope of this public health problem. However, to develop effective prevention measures, we need to understand the types of foods contributing to the problem.

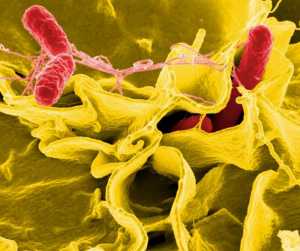

Previously, IFSAC developed foodborne illness source attribution estimates for 2012, based on a new method. The estimates used outbreak data from 1998 through 2012 for four priority pathogens, Salmonella, Escherichia coli O157, Listeria monocytogenes (Lm), and Campylobacter. IFSAC described this method and the estimates for 2012 in a report and at a public meeting.

For this latest report, IFSAC derived the estimates for 2013 using the same method used for the 2012 estimates, with some modifications, such as removing Dairy from the attribution for Campylobacter. The data came from 1,043 foodborne disease outbreaks that occurred from 1998 through 2013 and for which each confirmed or suspected implicated food fell into a single food category. The method relies most heavily on the most recent five years of outbreak data (2009–2013). Foods are categorized using a published scheme IFSAC created to classify foods into 17 categories that closely align with the U.S. food regulatory agencies’ classification needs.

MedicalResearch.com: What are the main findings?

Response: The report (based on outbreak data from 1998 through 2013) found that:

Salmonella illnesses came from a wide variety of foods.

Salmonella illnesses were broadly attributed across multiple food categories. More than 75% of Salmonella illnesses were attributed to seven food categories: seeded vegetables (such as tomatoes), eggs, chicken, other produce (such as nuts), pork, beef, and fruits.

- coli O157 illnesses were most often linked to vegetable row crops (such as leafy greens) and beef.

More than 75% of illnesses were linked to vegetable row crops and beef.

Listeria monocytogenes illnesses were most often linked to fruits and dairy products.

More than 75% of illnesses were attributed to fruits and dairy products, but the rarity of Listeria monocytogenes outbreaks makes these estimates less reliable than those for other pathogens.

Non-Dairy Campylobacter illnesses were most often linked to chicken.

Almost 80% of non-Dairy foodborne illnesses were attributed to chicken, other seafood (such as shellfish), seeded vegetables, vegetable row crops, and other meat/poultry (such as lamb or duck). An attribution percentage for Dairy is not included because, among other reasons, most foodborne Campylobacter outbreaks were associated with unpasteurized milk, which is not widely consumed, and we think these over-represent Dairy as a source of Campylobacter illness. Moreover, an analysis of 38 case-control studies of sporadic campylobacteriosis found a much smaller percentage of illnesses attributable to consumption of raw milk than chicken. Removing Dairy illnesses from the calculations highlights important sources of illness from widely consumed foods, such as Chicken.

MedicalResearch.com: What should readers take away from your report?

Response: IFSAC helps CDC and the regulatory agencies coordinate methods and attribution estimates to prioritize food safety initiatives, interventions, and policies for reducing foodborne illnesses.

This report uses data from 1998 through 2013 to provide outbreak-based estimates for 2013 of the percentage of illnesses caused by four priority pathogens, assigning illnesses to each of 17 food categories. The attribution of Salmonella illnesses to multiple food categories suggests that interventions designed to reduce illnesses from these pathogens need to target a variety of food categories. In contrast, E. coli O157 and Lm illnesses were attributed to fewer food categories, suggesting more focused interventions. Like Salmonella, Campylobacter illnesses were broadly attributed across multiple food categories. However, Campylobacter attribution is challenging given issues with the Dairy food category.

The 2012 and 2013 estimates achieve IFSAC’s goals of using improved methods to develop estimates of foodborne illness source attribution for priority pathogens and of achieving consensus that these are the best current estimates for CDC, FDA, and USDA/FSIS to use in their food safety activities. These estimates can also help scientists; federal, state, and local policy-makers; the food industry; consumer advocacy groups; and the public assess whether prevention measures are working.

MedicalResearch.com: What recommendations do you have for future research as a result of this work?

Response: As more data become available and methods evolve, attribution estimates may improve. Identifying the most common food sources responsible for specific foodborne illnesses will enhance IFSAC’s efforts to inform and engage stakeholders, and further their ability to assess whether prevention measures are working. IFSAC continues to enhance attribution efforts by working on projects that address limitations identified in this report, including further exploration of Campylobacter illnesses and inclusion of foods with ingredients assigned to more than one food category into attribution estimates.

IFSAC’s ongoing and future research plans are detailed in our 2017-2021 Strategic Plan and 2017 Action Plan, both of which are available on the IFSAC webpage: https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/ifsac/overview/strategic-plan.html and https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/pdfs/IFSAC-Draft-Action-Plan_FINAL.pdf.

MedicalResearch.com: Is there anything else you would like to add?

Response: These estimates should not be interpreted as suggesting that all foods in a category are equally likely to transmit pathogens. Caution should also be exercised when comparing estimates across years, as a decrease in a percentage may result, not from a decrease in the number of illnesses attributed to that food, but from an increase in illnesses attributed to another food. The analyses show relative changes in percentage, not absolute changes in attribution to a specific food. Therefore, we advise using these results with other scientific data for decision-making.

No disclosures.

Citations:

IFSAC publication: Foodborne illness source attribution estimates for 2013 for Salmonella, Escherichia coli O157, Listeria monocytogenes, and Campylobacter using multi-year outbreak surveillance data, United States

The full report is available here: https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/pdfs/IFSAC-2013FoodborneillnessSourceEstimates-508.pdf

MedicalResearch.com is not a forum for the exchange of personal medical information, advice or the promotion of self-destructive behavior (e.g., eating disorders, suicide). While you may freely discuss your troubles, you should not look to the Website for information or advice on such topics. Instead, we recommend that you talk in person with a trusted medical professional.

The information on MedicalResearch.com is provided for educational purposes only, and is in no way intended to diagnose, cure, or treat any medical or other condition. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health and ask your doctor any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. In addition to all other limitations and disclaimers in this agreement, service provider and its third party providers disclaim any liability or loss in connection with the content provided on this website.

Last Updated on January 22, 2018 by Marie Benz MD FAAD