31 Mar Which Patients With Advanced Respiratory Disease Die in the Hospital?

MedicalResearch.com Interview with:

Dr Sabrina Bajwah

MBChB MRCGP MSc MA PhD

Consultant Palliative Medicine, King’s College NHS Foundation Trust

Honorary Senior Lecturer

King’s College London

Cicely Saunders Institute, Department of Palliative Care, Policy and Rehabilitation

London, UK

MedicalResearch.com: What is the background for this study?

Response: Where people die is often important to them and their families, as well as being important for planning health care services. Most people want to die at home, but instead most die in hospital. While the trends have been studied in cancer, other diseases, such as respiratory, are rarely looked at even though they are common and increasing causes of death.

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and Interstitial Pulmonary Diseases (IPD) are common respiratory conditions. Both conditions result in a high use of hospital services, especially among people in advanced stages. This leads to high healthcare costs.1 In the UK in 2010, it is estimated that IPD costs £16.2 million per year in hospitalisations.2 The NHS spends more than £810 million annually managing COPD, with inpatient stays accounting for around £250 million annually.

Understanding which factors affect place of death is vital for planning services and improving care, especially given our ageing population, rising chronic diseases and the high costs of hospital admissions. Strategies in many countries have sought to improve palliative care and reduce hospital deaths for non-cancer patients, but their effects are not evaluated.

We aimed to determine the trends and factors associated with dying in hospital in COPD and IPD, and the impact of a national end of life care (EoLC) strategy3 to reduce deaths in hospital. This study analysed a national data set of all deaths for COPD and IPD, covering 380,232 people over 14 years.

MedicalResearch.com: What are the main findings?

Response: Over 14 years, 380,232 people died from COPD (334,520) or IPD (45,712). Deaths from COPD and IPD increased by 0.9% and 9.2% annually respectively. Death in hospital was most common: 67% COPD, 70% IPD. Dying in hospice was rare (0.9% COPD, 2.9% IPD). After a plateau in 2004-5, hospital deaths fell (PRs 0.92-0.94).

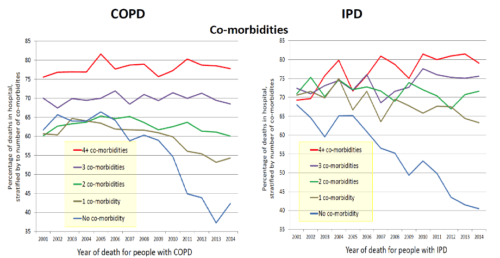

Comorbidities and deprivation independently increased the chances of dying in hospital, with larger effects in IPD (PRs 1.01-1.55) than COPD (PRs 1.01-1.39) and dose response gradients. The impact of multimorbidity increased over time; hospital deaths did not fall for people with ≥2 co-morbidities in COPD, nor ≥1 in IPD.

Living in rural areas (PRs 0.94-0.94) or outside London (PRs 0.89-0.98) reduced the chances of hospital death. In IPD, increased age reduced the likelihood of hospital death (PR 0.81,≥85 versus ≤54 years); divergently in COPD, being aged 65-74 years was associated with increased hospital death (PR versus ≤54 years 1.13). The independent effects of gender and marital status differed for COPD versus IPD (PRs 0.89-1.04); in COPD hospital death was associated with being married.

MedicalResearch.com: What should readers take away from your report?

Response: There was no fall in hospital deaths for people with multimorbidity, and that disparity widened over time. In the UK, the number of people with three or more long-term conditions is predicted to rise from 1.9 million in 2008 to 2.9 million in 2018, requiring a major increase in healthcare expenditure.

MedicalResearch.com: What recommendations do you have for future research as a result of this study?

Response: It is essential that future strategies for end of life and palliative care directly target those at highest risk, especially with multi morbidity, and in deprived areas and cities – this may require different approaches.

The quality of palliative care is important in all places where people are cared for; home, hospital and hospices. Finding an alternative to hospital for people with multimorbidity may be especially difficult, and may require in-patient beds in hospices, palliative care beds in hospitals or different, more intensive support at home. Future research should focus on these areas.

References:

1.Barnes PJ. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effects beyond the lungs. PLoS Med. 2010;7(3), e1000220.

2.Navaratnam V, Fogarty AW, Glendening R, McKeever T, Hubbard RB. The increasing secondary care burden of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: hospital admission trends in England from 1998 to 2010. Chest. 2013;143(4):1078–84.

3.Department of Health. National End of Life Care Strategy. London: Department of Health; 2008.

MedicalResearch.com: Thank you for your contribution to the MedicalResearch.com community.

Citation:

Note: Content is Not intended as medical advice. Please consult your health care provider regarding your specific medical condition and questions.

More Medical Research Interviews on MedicalResearch.com

[wysija_form id=”5″]

Last Updated on April 2, 2017 by Marie Benz MD FAAD