15 Aug How Our Brain Lets Us Believe What We Want To Believe

MedicalResearch.com Interview with:

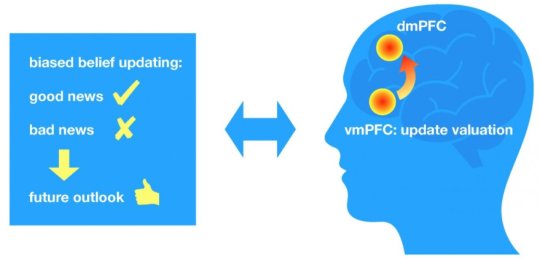

People demonstrate biased belief updating: They tend to regard good news indicating that personal risks are lower than expected, and to disregard bad news indicating that personal risks are higher than expected. Kuzmanovic and colleagues show that this optimism bias depends on the update valuation by the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) and its influence on the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC) associated with self-referential reasoning.

Credit: Bojana Kuzmanovic

Dr. Bojana Kuzmanovic PhD

Max Planck Institute for Metabolism Research

Translational Neurocircuitry Group

Cologne, Germany

MedicalResearch.com: What is the background for this study? What are the main findings?

Response: Do our beliefs depend on what we want to believe? Until now, researchers failed to show how interactions between brain regions mediate the influence of motivation to adopt desirable notions on ongoing reasoning. Our study used optimized design and analyses to rule out alternative explanations and to identify underlying neurocircuitry mechanisms.

MedicalResearch.com: What are the main findings?

Response: First, we demonstrated that people’s belief formation behavior depends on their preferences. When people were asked to reconsider their beliefs about their future outcomes, they tended to rely more strongly on good news and to disregard bad news.

Second, we showed that favorable belief updating activated the brain valuation system known to be responsive to rewards such as food or money (ventromedial prefrontal cortex, vmPFC). That is, the valuation system was activated when participants incorporated good news to improve their risk estimates, and when they disregarded bad news to avoid a worsening of their risk estimates.

And third, the valuation system influenced other brain regions that are involved in deriving conclusions about oneself (dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, dmPFC). Importantly, the more participants were biased in their belief formation behavior, the stronger was the engagement and the influence of the valuation system.

The influence of the valuation system on the reasoning system helps to understand how motivation can affect reasoning. It supports the idea that memories and knowledge we recall to form our beliefs are selected in such a way as to yield the desired conclusions. For example, when we wish to convince ourselves that our risk of having a heart attack is low although federal statistics indicate a higher risk, we might recall our healthy life style but not our family history of heart-related diseases, or neglect the fact that the federal population may have a comparable life style.

MedicalResearch.com: What should readers take away from your report?

Response: The influence of our desires and preferences on reasoning is powerful and operates without our awareness. The same brain systems that reinforce our efforts to maximize rewards such as food and money also reinforce specific strategies for constructing beliefs. Thus, under high uncertainty, as soon as we hold a preference for one conclusion over another, we are in danger of making a biased judgment.

As preferences are independent of expertise, the danger applies both to experts and laymen. We can benefit from this pleasant self-enhancing effect as long as our judgments do not have severe consequences. However, when we make important decisions, we should be aware of our constrained reasoning and apply strategies to increase objectivity.

MedicalResearch.com: What recommendations do you have for future research as a result of this work?

Response: Future research should focus on conditions that modulate the influence of motivations on reasoning. While there are already intriguing findings showing modulations dependent on development stages and psychiatric conditions such as depression and autism, little is known about the influence of metabolic states and conditions.

Reward-related brain circuits are closely intertwined with homeostatic circuits that regulate energy demands based on satiety and hunger signals. Thus, recent research showing decreased impulsivity after food intake and alterations of such regulations in individuals with insulin-resistance should be further extended.

Citation:

Bojana Kuzmanovic, Lionel Rigoux, Marc Tittgemeyer. Influence of vmPFC on dmPFC Predicts Valence-Guided Belief Formation. The Journal of Neuroscience, 2018; 0266-18 DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0266-18.2018

[wysija_form id=”3″]

[last-modified]

The information on MedicalResearch.com is provided for educational purposes only, and is in no way intended to diagnose, cure, or treat any medical or other condition. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health and ask your doctor any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. In addition to all other limitations and disclaimers in this agreement, service provider and its third party providers disclaim any liability or loss in connection with the content provided on this website.

Last Updated on August 15, 2018 by Marie Benz MD FAAD