01 Nov The Appendix May Play Role in Initiation of Parkinson’s Disease

MedicalResearch.com Interview with:

Dr. Labrie

Viviane Labrie, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor

Center for Neurodegenerative Science

Van Andel Research Institute

Grand Rapids, Michigan

MedicalResearch.com: What is the background for this study?

Response: Our lab has an interest in the early events and initiation of neurodegenerative diseases. Parkinson’s disease for a long time was thought to be a movement disorder driven by the destruction of dopamine neurons in a specific area of the brain, the substantia nigra. In the last 10 years it has become evident that Parkinson’s disease is not just a movement disorder but hosts a whole range of non-motor systems. One of the most common non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s patients is issues with the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. GI symptoms often occur early in Parkinson’s disease; for many patients, GI symptoms precede the onset of motor symptoms by as many as 2 decades. Moreover, the GI is not only involved in the early signs of Parkinson’s but has been proposed to be a place in the body where Parkinson’s disease begins.

The hallmark pathology of Parkinson’s disease in the brain is Lewy bodies, which contains a clumped form of a protein called alpha-synuclein. There is evidence that Parkinson’s disease pathology, this clumped alpha-synuclein protein, is detectable in the GI tract, even many years before the onset of Parkinson’s motor symptoms. Clumped alpha-synuclein is also capable of traveling across nerve cells. There is evidence that clumped alpha-synuclein can travel up the nerve that connects the GI tract to the brain and enter the brain. This could be disastrous because clumped alpha-synuclein can seed and spread in the brain, which has neurotoxic effects and can eventually lead to Parkinson’s disease. In fact, in the brain of Parkinson’s patients, one of the first places where alpha-synuclein clumps are detected is at the terminal where the gut nerve connects to the brain, and this pathology advances from this point to other brain areas as the disease progresses.

This intriguing connection of the GI tract to the early processes of Parkinson’s disease had us interested in trying to understand how the gut could be involved in triggering Parkinson’s. But the GI tract is a very big place, and we first asked ourselves, where should we look to better understand GI involvement in Parkinson’s disease?

MedicalResearch.com: What are the main findings?

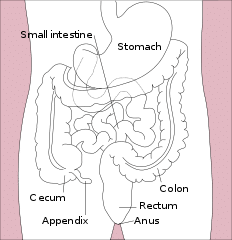

Response: We turned our attention to the vermiform appendix. This is a tissue that most people consider to be a useless organ, it’s attached to the large intestine, and its removed as a very common surgical practice.

But we thought the appendix might be important to GI origins of Parkinson’s disease because it plays a role in immune system regulation in the GI tract. Inflammation has been linked to Parkinson’s disease and the appendix is actually an immune tissue that is responsible for the sampling and monitoring of pathogens, and will raise immune responses. Changes in the microbiome, the gut bacteria, have also been observed in Parkinson’s disease and the appendix is also been shown to be a site that is involved in the storage and regulation of gut bacteria.

So we embarked on a full study of the role of the appendix in Parkinson’s disease.

First, we performed two epidemiological analyses using large medical record datasets to examining the effect of removing the appendix on Parkinson’s disease risk and development. We found that an appendectomy was linked to a nearly 20% decrease in risk for developing Parkinson’s disease in a general population. Among people who did develop Parkinson’s disease we found that the age of onset was delayed by an appendectomy, on average by 3.6 years. This suggest that an appendectomy is associated with a decreased risk for Parkinson’s in the general population and will delay the progression in patients whom develop Parkinson’s disease.

Next, we examined the appendix of healthy individuals and found a remarkable abundance of clumped forms of alpha-synuclein in the appendix. This is important because clumped alpha-synuclein was previously attributed to Parkinson’s; and now we find that — in the appendix — clumped alpha-synuclein is not a unique feature of Parkinson’s disease but is present in everyone.

Then we performed biochemical studies detailing the forms of alpha-synuclein in the appendix. We found that there were shortened forms of alpha-synuclein present in the appendix that were prone to extremely rapid clumping and very much resembled those seen in the Parkinson’s disease brain.

MedicalResearch.com: What should readers take away from your report?

Response: Together our study suggests that the appendix may be a tissue site that plays a role in the initiation of Parkinson’s disease. We have shown that clumped alpha-synuclein is present in the appendix of all of us, and we think that if in rare events it were to escape the appendix and enter the brain this could lead to Parkinson’s disease. This is important for how we think of Parkinson’s origins and treatments, because preventing excessive alpha-synuclein clump formation in the appendix and its departure from the gut could be useful for new therapies. In other words, there is potential for GI tract-based therapies that block the formation and spread of alpha-synuclein clumps as future early and preventative treatments for Parkinson’s disease.

We are not saying that having an appendix causes Parkinson’s disease and that all people should go out and remove their appendix. What we are saying is that the appendix is a tissue site that contains a lot forms of alpha-synuclein that are associated with PD, even in healthy people.

But that location is everything. Alpha-synuclein aggregates are normal in the appendix, but in very rare instances, we think that if allow to escape and go to the brain could be disease causing. We think that what actually distinguishes a person that goes onto develop Parkinson’s from one that does not is not the presence of this pathology but rather the factors that trigger departure from the appendix, its spread to the brain and its neurotoxicity.

This brings new insight into the origins of the disease and could help improve future therapies for this devastating neurodegenerative disease.

MedicalResearch.com: What recommendations do you have for future research as a result of this work?

Response: Next steps for physicians (and public):

- Learn about the early signs of Parkinson’s disease (the non-motor symptoms) and be vigilant for these. For their patients that already have Parkinson’s they should ask their patients about these non-motor symptoms and consider treating these in addition to the motor symptoms

- GI inflammation has been associated with Parkinson’s disease risk, and managing GI inflammation has been proposed to reduce the risk of Parkinson’s

- Be aware that Parkinson’s may start outside of the brain, in the GI tract –specifically the appendix– may be a site of origin.

Disclosure: Conflicts of interest are detailed in the paper.

Citation:

Bryan A. Killinger, Zachary Madaj, Jacek W. Sikora, Nolwen Rey, Alec J. Haas, Yamini Vepa, Daniel Lindqvist, Honglei Chen, Paul M. Thomas, Patrik Brundin, Lena Brundin, Viviane Labrie. The vermiform appendix impacts the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. Science Translational Medicine, 2018; 10 (465): eaar5280 DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aar5280

[wysija_form id=”3″]

[last-modified]

The information on MedicalResearch.com is provided for educational purposes only, and is in no way intended to diagnose, cure, or treat any medical or other condition. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health and ask your doctor any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. In addition to all other limitations and disclaimers in this agreement, service provider and its third party providers disclaim any liability or loss in connection with the content provided on this website.

Last Updated on November 1, 2018 by Marie Benz MD FAAD