02 Aug Genes From Dad Influence How Mom Cares for Babies

MedicalResearch.com Interview with:

Professor Rosalind John

Professor Rosalind John

Head of Biomedicine Division, Professor

School of Biosciences

Cardiff University

Cardiff UK

MedicalResearch.com: What is the background for this study? What are the main findings?

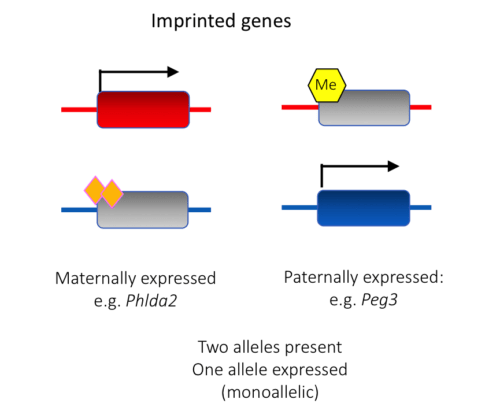

Response: I have been studying a really remarkable family of genes called “imprinted genes” for the last 20 years. For most genes, we inherit two working copies — one from our mother and one from our father. But with imprinted genes, we inherit only one working copy – the other copy is switched off by epigenetic marks in one parent’s germline. This is really odd because we are all taught at school that two copies of a gene are important to protect us against mutations, and much safer than only one copy. So why turn off one copy?

When my research group were studying these genes in mice, we found out that one of them, called Phlda2, plays an important role in the placenta regulating the production of placental hormones. Placental hormones are critically important in pregnancy as they induce adaptations in the mother required for healthy fetal growth. There was also some indirect evidence that placental hormones play a role in inducing maternal instinct. Women are not born with a maternal instinct – this behaviour develops during pregnancy to prepare the mother-to-be for the new and demanding role of caring for her baby. This led to my idea that this gene expressed in the offspring’s placenta could influence maternal behaviour, which was entirely novel.

Until now direct experimental evidence to support the theory that placental hormones trigger this “motherly love” by acting directly on the brain of the mother has been lacking. To test the theory that our imprinted gene could influence the mother’s behaviour by regulating placental hormones, we generated pregnant mice by IVF carrying embryos with different copies of Phlda2. We used IVF to keep all the mothers genetically identical. This resulted in genetically identical pregnant female mice exposed to different amounts of placental hormones – either low, normal or high.

We found that female mice exposed in pregnancy to low amounts of placental hormones were much more focused on nest building (housekeeping) and spent less time looking after their pups or themselves than normal mice. In contrast, female mice exposed to high placental hormones neglected their nests and spent more time looking after their pups and more time self-grooming. We also found changes in the mother’s brain before the pups were born so we know that the change in priorities started before birth.

MedicalResearch.com: What should readers take away from your report?

Response: This study is important because it shows, for the first time, that genes from the dad expressed in the placenta influence the quality of care mothers gives to their offspring. Perhaps more significantly, this study highlights the importance of a fully functional placenta for high quality maternal care.

We have shown in a mouse model that genes in the placenta and placental hormones are important for priming maternal nurturing in an animal model. Human placenta have the same imprinted genes and also manufactures placental hormones. It is possible that problems with the placenta could misprogram maternal nurturing in a human pregnancy and these mothers may not bond well with their newborn. It is also possible that problems with the placenta could contribute to depression in mothers. We are all familiar with postnatal depression but many more mothers experience depression in pregnancy with 1 in 7 mothers reporting clinically significant symptoms.

MedicalResearch.com: What recommendations do you have for future research as a result of this work?

Response: After we found out that Phlda2 could influence maternal behaviour in mice, we asked whether there were changes in this gene in human placenta from pregnancies where women were either diagnosed with clinical depression or self reported depression in pregnancy. Phlda2 seems to be OK but we found another gene that belongs to the same imprinted gene family called PEG3 that is expressed at lower than normal levels in women with depression. Strangely, this seems to only be in placenta from boys.

MedicalResearch.com: Is there anything else you would like to add?

Response: To explore this further, we have just started our own human cohort study called “Grown in Wales” at Cardiff University focused on prenatal depression. We are now looking at placental hormones in the mother’s blood and gene expression in the placenta to test the idea that the genes we are studying in mice are misregulated in the placenta of pregnancies where the mothers suffer with depression. This work is now funded by the Medical Research Council.

Citation:

Maternal care boosted by paternal imprinting in mammals

D. J. Creeth, G. I. McNamara,, S. J. Tunster, R. Boque-Sastre,, B. Allen,, L. Sumption, J. B. Eddy,A. R. Isles, R. M. John PLOS

Published: July 31, 2018

[wysija_form id=”3″]

[last-modified]

The information on MedicalResearch.com is provided for educational purposes only, and is in no way intended to diagnose, cure, or treat any medical or other condition. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health and ask your doctor any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. In addition to all other limitations and disclaimers in this agreement, service provider and its third party providers disclaim any liability or loss in connection with the content provided on this website.

Last Updated on August 2, 2018 by Marie Benz MD FAAD