05 Feb Deaf Children With Cochlear Implants Learn New Words Faster

MedicalResearch.com Interview with:

Niki Katerina Vavatzanidis MSc

Department of Neuropsychology

Max Planck Institute for Human and Cognitive Brain Science

Leipzig, Germany

Technische Universität Dresden, Germany

MedicalResearch.com: What is the background for this study? What are the main findings?

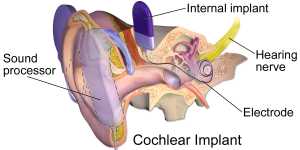

Response: Cochlear implants (CIs) are a way of providing hearing to sensorineural deaf individuals. The implant works by first picking up sounds from the environment and transforming them into an electric signal. Via an array of electrodes the implant then transmits the signal directly to the auditory nerve, which then leads to auditory sensations in the brain.

In our study, we were interested to see how language acquisition is affected when language immersion occurs at an untypically late age. Children with cochlear implants that grow up in exclusively or predominantly hearing environments will have their first language encounter at the time of implantation, which nowadays is roughly between the age of one and three. Besides the later starting point in language acquisition, children with CIs are facing a compromised input quality compared to typical hearing.

We know from typically hearing children that it is around the age of 14 months that their vocabulary becomes robust enough to react to name violations. That is, when a picture is labelled incorrectly, their brain waves will display with the so-called N400 effect. In our study we were interested whether children with CIs would also show the N400 effect and if so, how many months of hearing experience are necessary. We measured the brain activity of children implanted between the age of one and four at three time points: 12, 18, and 24 months after implant activation. To our surprise, congenitally deaf children whose only language input had been via the cochlear implant already displayed the N400 effect after 12 months of language immersion, i.e. earlier than seen in typically hearing children.

MedicalResearch.com: What should readers take away from your report?

Response: Children seem to compensate for the late start of language acquisition, probably because other cognitive domains are more mature at the time of language onset. Better memory structures are likely to ensure that learned words are better retained and the world knowledge that children have acquired in the absence of language probably provides a sort of “template” that then can be quickly filled with the appropriate labels. (An example for acquired world knowledge could be that animals like cats and dogs move and produce sounds, while furniture items do not. This creates distinct categories for animals and furniture even if the categories do not carry linguistic labels.)

Our results thus indicate that children with cochlear implants are faster in word acquisition, an important prerequisite for eventually catching up with their typically hearing age peers.

MedicalResearch.com: What recommendations do you have for future research as a result of this work?

Response: It would be extremely valuable to see this study replicated. Beyond that, we are currently extending the study to see how early the effect emerges, i.e. how many months of language immersion the older brain needs in order to establish robust semantic relationships.

Also of importance, however, would be to see how language evolves beyond the vocabulary domain. Other language domains, especially grammar, might be harder to compensate and they might be more affected by the compromised auditory input. In addition, a small group of children who had poor language test results after 24 months of implant use did not display an N400 effect at any of the test points. Understanding the reasons for the missing effect might help finding better therapeutic interventions for these children.

Citations:

Establishing a mental lexicon with cochlear implants: an ERP study with young children

Niki K. Vavatzanidis, Dirk Mürbe, Angela D. Friederici & Anja Hahne

Scientific Reports volume 8, Article number: 910 (2018)

doi:10.1038/s41598-017-18852-3

[wysija_form id=”3″]

The information on MedicalResearch.com is provided for educational purposes only, and is in no way intended to diagnose, cure, or treat any medical or other condition. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health and ask your doctor any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. In addition to all other limitations and disclaimers in this agreement, service provider and its third party providers disclaim any liability or loss in connection with the content provided on this website.

Last Updated on February 6, 2018 by Marie Benz MD FAAD