27 Feb Evidence-Based Medicine Up in Smoke? An Analysis of the Qualifying Conditions for Medical Marijuana

MedicalResearch.com Interview with:

Elena Stains

Elena Stains

Medical Student

Department of Medical Education

Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine

Scranton, PA

MedicalResearch.com: What is the background for this study?

Response: In 2019 to 2020, 2.5% of Americans reported using cannabis for medical needs, compared to 1.2% in 2013-2014, representing a 12.9% annual increase1. Forty states and the District of Columbia have legislation for some form of medical cannabis (MC) in 2024. Because MC is not federally legalized, each state creates its own legislation on the conditions that qualify a person for MC, without any standardized process to determine what qualifying conditions (QC) are proven to be aided by MC. Thus, the QCs chosen by states vary widely. Common QCs include cancer, dementia, and PTSD.

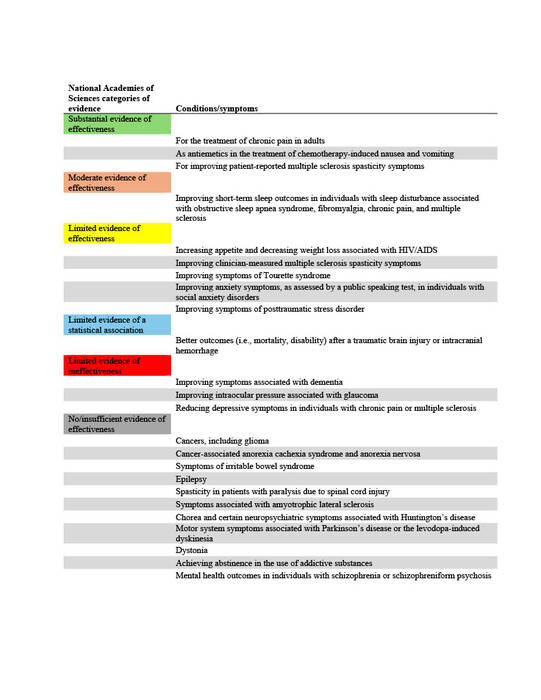

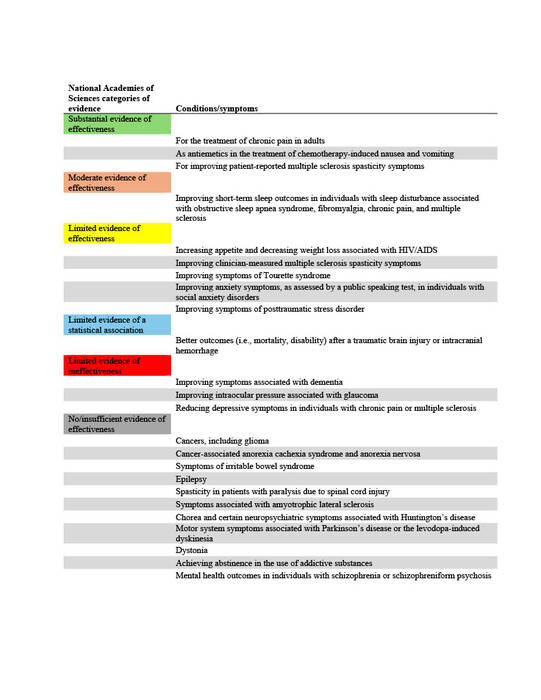

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NAS) published a report in 2017 on the evidence for the therapeutic effects of cannabis and cannabinoids for over twenty conditions2. This report reviews the evidence of effectiveness of medical cannabis for the most common QCs chosen by states. The researchers at Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine aimed to compare the evidence found by the NAS report with the QCs of 38 states (including the District of Columbia) in both 2017 and 2024. QCs were categorized based on NAS-established level of evidence: limited, moderate, or substantial/conclusive evidence of effectiveness, limited evidence of ineffectiveness, or no/insufficient evidence to support or refute effectiveness (Table 1).

MedicalResearch.com: What are the main findings?

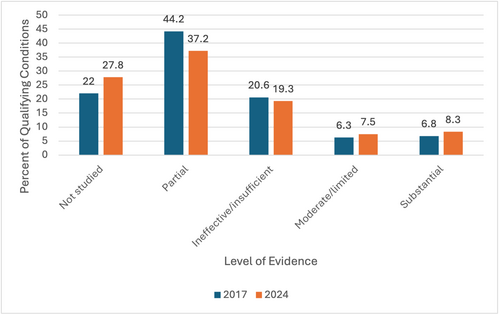

Response: Of the 31 states that had legislation for medical cannabis in 2017, 25 had at least one QC with substantial or conclusive evidence of effectiveness. However, only 6.8% of the country’s QCs in this year met this standard. In 2024, there was marginal improvement—37 out of 38 states with MC had at least one QC with substantial/conclusive evidence. Yet, only 8.3% of QCs were backed by at least substantial evidence (Figure 1). This increase was not significant.

The number of qualifying conditions chosen by each state varied widely, in line with discussion above that there lacks a regulatory framework across states for establishing QCs. In 2024, South Dakota had the fewest QCs at 5, while Illinois had ten times that at 52. Ten states included with their QC list the ability of providers to recommend MC for any condition that they believe it would be beneficial. Five states (District of Columbia, Maine, New York, Oklahoma, Virginia) required no QCs whatsoever.

Of the 20 most popular QCs in the country in 2017 and 2024, only one (chronic pain) was categorized by the NAS as having substantial evidence for effectiveness. However, seven (Amyotropic Lateral Sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy, glaucoma, Huntington’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, spastic spinal cord damage) were rated as either ineffective or insufficient evidence.

In 2024, 90.9% of states had at least one QC that was not studied in the NAS report. Most states also had many QCs that were either too vaguely or broadly labeled or overlapped with several conditions studied by the NAS report, and these QCs were labeled “partial” by researchers. Thirty-seven percent of the country’s QCs were partial.

Table 1. Categories of evidence established by the 2017 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NAS) report.

Figure 1. Percent of qualifying conditions (QC) in the United States with each level of evidence in 2017 and 2024.

MedicalResearch.com: What should readers take away from your report?

Response: This report is the first of its kind as it explores the qualifying conditions of every state in the United States and compares them to a high-quality foundation of evidence.2 This report is also unique in that it compares the changes in QCs over time—what states looked like in the year of the NAS publication versus how they may have changed to conform to research-based practices.

Through the results of this research, the authors have shown that in 2017 QCs listed by states were largely unproven or unresearched. By 2024, states had not adjusted their QCs to align with major sources of evidence like that published by the NAS.2 There was no significant increase in QCs with substantial/conclusive evidence, moderate evidence, or limited evidence from 2017 to 2024. There was not even a significant change in QCs with evidence of ineffective, suggesting states added to their QC lists from all groups of evidence (including “not studied” and “partial”) and did not weed out any QCs found to be ineffective or poorly studied.

MedicalResearch.com: What recommendations do you have for future research as a results of this study?

Response: Our research provides detailed information about QCs and how many states list them. However, further research into how many patients use MC for each condition would help to determine the impact of the 34 states that allow MC use for QCs with evidence of ineffectiveness. For example, according to a study of 19 states in 2022, the most reported use for MC was chronic pain, used by 48.4% of patients3. Chronic pain does fall under the category of substantial evidence.

MedicalResearch.com: Is there anything else you would like to add? Any disclosures?

Response: Policymakers in the United States can benefit from understanding the results of this study. Although legislators have the difficult job of creating policy for a pharmaceutical substance that is not yet well understood, lawmakers should be doing their best to always incorporate evidence-based medicine into MC policy.

New Report

Stains EL, Kennalley AL, Tian M, Boehnke KF, Kraus CK, Piper BJ. Medical Cannabis in the United States: Comparing 2017 and 2024 State Qualifying Conditions to the 2017 National Academies of Sciences Report. Mayo Clinic Proceedings: Innovations, Quality & Outcomes. 2025;9(2):100590. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2025.100590

Citations:

- Rhee TG, Rosenheck RA. Increasing Use of Cannabis for Medical Purposes Among U.S. Residents, 2013-2020. Am J Prev Med. 2023;65(3):528-533. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2023.03.005

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (U.S.), ed. The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research. The National Academies Press; 2017.

- Boehnke KF, Sinclair R, Gordon F, et al. Trends in U.S. Medical Cannabis Registrations, Authorizing Clinicians, and Reasons for Use From 2020 to 2022. Ann Intern Med. Published online April 9, 2024. doi:10.7326/M23-2811

——————–

The information on MedicalResearch.com is provided for educational purposes only, and is in no way intended to diagnose, cure, or treat any medical or other condition.

Some links may be sponsored. Products are not warranted or endorsed.

Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health and ask your doctor any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. In addition to all other limitations and disclaimers in this agreement, service provider and its third party providers disclaim any liability or loss in connection with the content provided on this website.

Last Updated on February 27, 2025 by Marie Benz MD FAAD