MedicalResearch.com Interview with:

Daniel L. Worthley

MBBS (Hons), PhD, MPH, FRACP, AGAF

Gastroenterologist

Associate Professor

University of Adelaide

MedicalResearch.com: What is the background for this study?

Response: Cells are revolutionising healthcare, from modern faecal microbial transplantation in the gut to CAR-T cells fighting cancers, life healing life. Some aspects of cellular care are so entrenched in medicine that they are almost overlooked for the miraculous cellular therapies that they are, such as stem cell transplantation to treat haematological malignancies and, of course, in vitro fertilization, life creating life. Modern medicine is slowly, but surely, pivoting from pills to cells. Professor Siddhartha Mukherjeee, oncologist, scientist, and author, provides a beautiful thesis of this in his book Song of the Cell and in his TED talk on the cellular revolution in medicine (

https://youtu.be/qG_YmIPFO68?feature=shared). I was lucky enough to have trained with Sid as a post-doc at Columbia and this concept was really drummed into me. But, as a gastroenterologist, perhaps it was the bacterial cells, rather than the blood cells, that had most to offer in the management of bowel disorders? Around the same time, Professors Jeff Hasty, Tal Danino and Omar Din from UC San Diego had been inventing and publishing, in my opinion, the best bacterial engineering work that has ever been produced to specifically target cancer. I remember when we first reviewed their 2016 Nature paper in our lab meeting (

https://www.nature.com/articles/nature18930#citeas), it was like – “We gotta meet these guys!”. Through Tal, who was by then, working at Columbia, I was introduced to Jeff and I attended his lab meeting back in 2019. That was where our project began after a lab meeting in La Jolla. Rob Cooper had presented his work on horizontal gene transfer. Everything that comes out of Jeff’s lab is both practical and reproducible but also beautiful. Beautiful in a scientific self-evident way that instantly communicates the purpose, approach and outcomes of an experiment.

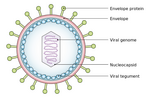

Rob’s presentation that day was a case-in-point. Rob was studying genes and gene transfer in bacteria (see part of Rob’s fascinating presentation here,

https://youtu.be/5nBsRF-BsA8?feature=shared). Genes are the fundamental unit of heredity and gene transfer (or inheritance) the process by which genes are passed from one cell to another. Genes may be inherited vertically when one cell replicates its DNA and divides into two, now separate, cells (reproduction). Genes are the stuff, and vertical gene transfer is the process, by which you receive your mother’s laugh and your father’s eyebrows. Genes may also, however, be inherited horizontally when DNA is passed between unrelated cells, outside of parent to offspring inheritance. Horizontal gene transfer is quite common in the microbial world. Certain bacteria can salvage genes from cell-free DNA found within its environment. This sweeping up of cell-free DNA, into a cell, is called natural competence. So, competent bacteria can sample their nearby environment and, in doing so, acquire genes that may provide a selective advantage to that cell. Like cellular panning for flecks of gold in a stream. After Rob’s presentation, Jeff, Rob and I started to discuss the possibilities. If bacteria can take up DNA, and cancer is defined genetically by a change in its DNA then, theoretically, bacteria could be engineered to detect cancer. Colorectal cancer seemed a logical proof of concept as the colorectal lumen is full of microbes and, in the setting of cancer, full of tumour DNA. When a biophysicist, a scientist and a gastroenterologist walk into a bar, after a lab meeting, this is what can happen! Professor Susi Woods and Dr Josephine Wright, superb cancer scientists from Adelaide, Australia, were quickly recruited in as essential founding members of the group. We all got to work. Australian and US grants, lots of experiments, early morning Zoom calls across the Pacific, inventing new animal models and approaches, i.e. a many year, iterative process of design-build-test-learn, that got us all to where we are now.

(more…)